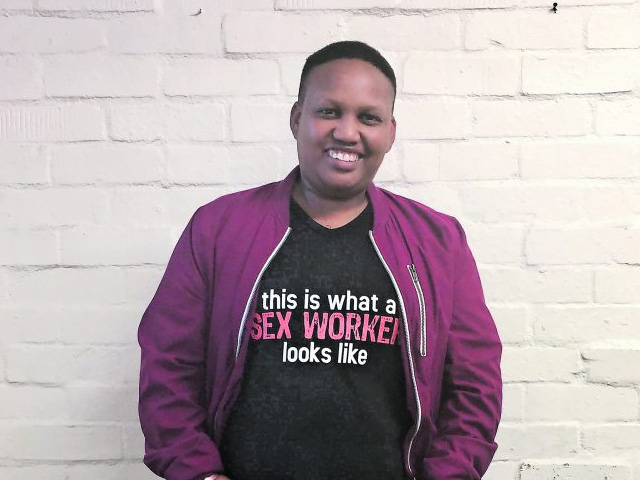

“My work has always been about trying to fight for social justice,” says activist and writer Malebo Sephodi. Her fierceness, proclivity to stand up for what she believes in and grace have earned her the title of “Lioness”, but she describes herself as an African feminist because she says she is steeped in her identity as an African woman.

Among her many pursuits, Sephodi runs a safe space for black women, where they can just be, called Lady Leader. The name is a play on words: “lady” comes from a certain behaviour imposed on women to follow decorum and “leader” is a title ladies were never meant to hold.

Lady Leader hosts a group of women — academics, community workers and entrepreneurs — who Sephodi mentors to become their best selves. It is a space for activists to take care of themselves, to be at peace and to cultivate joy. It has evolved over time, and was called Soul Ova until 2013.

Sephodi started Soul Ova in 2005 in response to gender-based violence. This was partly to deal with her own demons, and partly because she wanted to help those who had survived it. Soul Ova was a counselling organisation and support group that worked with shelters, dealing with cases of abuse nationwide. In an attempt to understand why men abused women, Sephodi tried to incorporate men into her counselling. She worked on a project at the Leeuwkop Maximum Correctional Centre to address the issue of violent masculinities in South Africa and held mentorship groups for boys.

In 2017 Sephodi published her book Miss Behave. It examines issues of power through the lens of a black woman in South Africa grappling with intersectionality, patriarchy, race, class, sexuality and gender — with gender being one of the most important elements in the book. “When we are conditioned to think gender is binary, we become quite prejudiced to anyone that does not conform to what our ideas of gender are,” Sephodi says. This births all kinds of prejudice, including sexism and homophobia.

Sephodi says the most important thing about her book is its accessibility: the way it explains political issues and concepts, particularly feminism, in accessible language. Sephodi says this is significant, because academic language often excludes and alienates certain groups of people.

The book challenges society’s deep-seated beliefs about what it means to be an obedient woman. It’s a reflection on Sephodi’s journey in misbehaviour that renounces the societal expectations imposed upon black women. — Shaazia Ebrahim