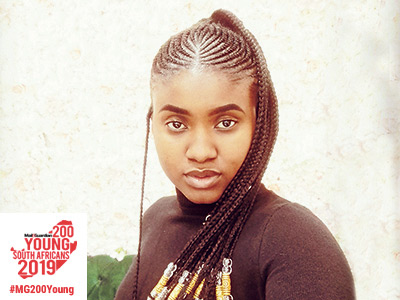

The 25-year-old advocacy firebrand, Tracey Malawana is also an Atlantic senior fellow for health equity in South Africa at Cape Town-based non-profit organisation Tekano. This means that she is an ambassador for change through initiating campaigns and transforming the state of health in South Africa, with the goal of attaining health equity for all.

Malawana is also the founder of the Health Living Alliance (Heala), which brings together like-minded organisations in a mission to improve the health of an increasingly obese South Africa. Heala’s overarching principle is to ensure that all South Africans have access to clean water and sufficient and healthy food. The organisation was established to reduce and prevent the alarming rate of non-communicable diseases in the country and also to raise awareness about the dangers of unhealthy food such as sugary drinks.

In her job as deputy secretary-general at Equal Education, Malawana serves as an internal and external political representative of the movement. She also supports all campaigns and ensures that all aspects of Equal Education’s work develop in accordance with the direction provided by the movement’s constitution and national congress resolutions, as she provides guidance and strategic direction on legal matters.

The two driving forces in her life ensure access to quality education and healthcare. And this explains the two highlights in her career: when the minimum norms and standards for school infrastructure was legislated in November 2013, “after years of protesting, picketing, night vigils, community hearings, demonstrations by members of Equal Education especially equalisers, who are school-aged children,” she remembers.

The second is when the sugary drinks tax was legislated in December 2017, “after 18 months of countless community, mass media and social media engagement, public hearings, submissions, demonstrations outside Parliament and petitioning,” she remembers.

“Even though I might not live to see that day but the coming generation shall not experience the struggles of my generation, they shall enjoy the benefits of our advocacy and pick their own struggles,” she says.

Coming from a working class she attended a township school and did not have resources similar to the schools in town or the ones they saw reflected on TV.

“I started questioning everything and feeding my consciousness by reading books,” says Malawana, and by doing so she learnt that she needn’t be complacent about the social ills in the country, and that she had the power to make a difference.—Welcome Lishivha

Twitter: @TraceyLulo