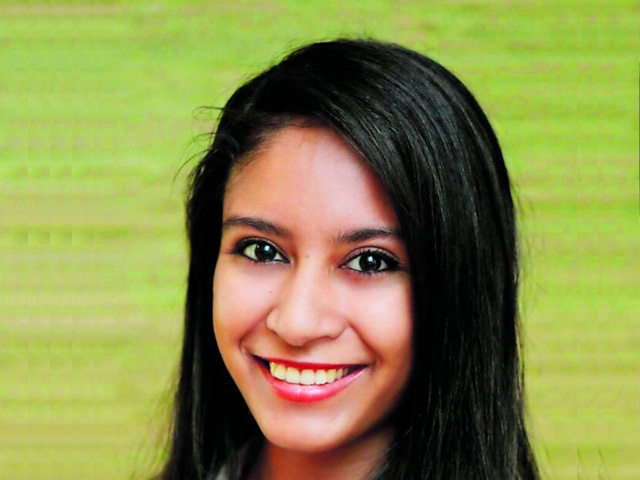

Zakeera Docrat is only 27 years old yet she has a list of qualifications and academic achievements that most people only achieve much later in life.

She was awarded her African language studies honours degree cum laude in 2014 and received full academic colours. This was followed by an LLB degree, an MA degree in African Language Studies (cum laude) in 2017 and she is now working towards her PhD in African languages (forensic linguistics/ language and law) under the auspices of the NRF SARChI Chair in the Intellectualisation of African Languages, Multilingualism and Education.

She has presented 13 conference papers globally, attended the International Forensic Linguistics Conference in Portugal with two papers later published and had an academic journal article and two chapters published in a book. Her editorial skills also extend to the Mail & Guardian, Daily Dispatch, City Press and The Conversation.

It seems language is in her blood. “I grew up in a home where my family were fully conversant in isiXhosa, the language of my birthplace and home, the Eastern Cape,” she says. “To this day there is a passion and excitement that ignites inside of me when I speak isiXhosa. It’s an incredible feeling and privilege to be able to communicate in an African language.”

By learning isiXhosa at the Diocesan School for Girls, Grahamstown from which I matriculated, there was an emphasis placed on the power of language in bringing people together and achieving social cohesion — and with the learning of a language you gain a culture.”

Docrat continues to be inspired by language and the power it has in changing people’s lives. She believes that languages have the power to contribute to the transformational agenda and is part of transformation.

“I unapologetically believe that language plays a central role in the legal system and that African language speakers are treated unfairly in comparison to English mother tongue speakers given that court proceedings take place in English and if you are not fully conversant in English you are reliant on the legal system’s interpretation services,” she says. “We need to ensure that legal practitioners and judicial officers are competent in the official languages of the province in which they practice.

I firmly believe it is possible. The Canadian legal model of the province of New Brunswick provides an example of linguistic inclusion and where language is seen as a resource and a right rather than a problem.” — Tamsin Oxford