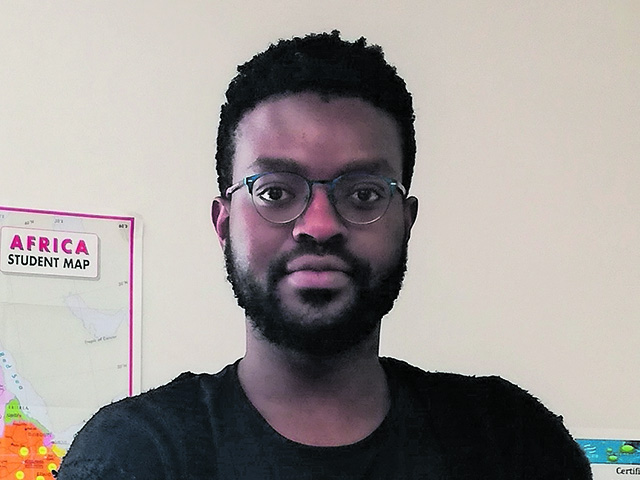

Coming from a family of teachers gave Piroshin Moodley the ability to see the importance of quality education as a “most basic human right”. This insight has lead him to work in child rights and education among some of the world’s most marginalised children.

Moodley has an undergraduate degree in anthropology from Rhodes University. He became the head of curriculum at the Unesco Global Peace Village in South Korea, where he worked on developing content on peace, values-based education and global citizenship for students of all ages. He then did a master’s in Human Rights and Humanitarian Action at the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po, France. As part of his degree he worked with Save the Children South Africa on a nationwide child protection campaign to curb violence against children in schools.

He then moved to Northern Uganda, where he works on a child rights and education project with Hope is Education International. Moodley’s organisation works to build and revitalise the education system in Northern Uganda’s village schools. The region has experienced one of the most brutal humanitarian crises worldwide, including mass human rights violations, torture, rape and the abduction of thousands of children.

Moodley’s team works with educators to improve teaching skills and curriculum development. The team is developing programmes to sensitise the community about the rights of children, prevention of early childhood marriage and child labour, the importance of keeping girl children in schools and childhood nutrition.

“By focusing on transferable skills, training and self-development we aim to create a generation of first-class educators, each of whom had the potential to transform the lives of thousands of children. While it is simplistic to say that education is a way out of poverty, it is certainly a solid first step,” he says.

Moodley said it always surprised him that South Africa allocated a higher proportion of its annual budget to basic education than most middle-income countries, and yet the South African education system is consistently ranked as one of the poorest worldwide.

“I think this speaks to a system which focuses more on rote learning and memorisation to produce measurable results, rather than a system which teaches our children how to be compassionate, actively engaged individuals who are part of a global citizenship.” — Rumana Akoob