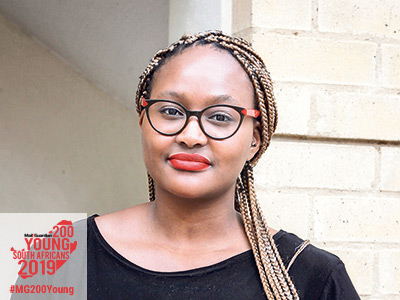

“I feel like I’ve always been an entrepreneur, looking at how I can get more involved,” 29-year-old Nomalungelo Stofile says of the two companies she has established.

Her father used to work for mining giant De Beers as the head of a training facility and he wanted her to get into the beneficiation of diamonds, taking them from their mined state to polished gems.

After he died in 2014, Stofile looked for a way to connect to him and she did this through diamonds.

She went for training on the technical aspects of cutting and polishing diamonds at the Diamond Education College and the State Diamond Trader.

While she was learning this entirely different skill set she was also hunting for funding and investment and only began to trade in earnest in 2018.

Stofile buys the diamonds from the State Diamond Trader, which means they are ethically sourced. This entails evaluating the rough diamond to see whether she will be able to make profit from them.

Despite the laborious process of cutting and polishing the gems, Stofile finds its relaxing and “highly beautiful” to see the end product.

“Depends on the source and clarity. This can take up to a few weeks and then you need to source a market for the diamond. I also sometimes work with a jeweller to create the final product, ”she says.

Stofile is passionate about beneficiation — refining — natural resources in South Africa and on a continent where raw products are often shipped abroad and refined there, and sold for far higher prices. Beneficiation and creating upstream industries from the dwindling mining sector has been a long held promise by the government, which it has failed to fully implement.

“It’s really important that we, as Africans, can benefit from the value of the resources on the continent,” she says.

Stofile works on the diamond refinement process herself but wants to start employing people for the time-intensive process while she juggles another high-end business — producing wine.

“I’m really passionate about wine as well. I didn’t know there were actually black people who made wine and it was sparked from travelling around Africa. I’d visit the DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo] and I’d be asked to source some South African wine.”

She spoke to wine farmers and discussed the possibility of getting into the business. It was then that she realised there were black-owned wine brands.

Stofile attended wine training courses to learn the basics of the industry, from vineyard to distribution.

A number of wine brands don’t own a farm and instead buy grapes from farmers. Her own wine brand, Bellascene Wines, works with a wine estate. But she’s looking into having her own cellar within two years.

Bellascene produces red wines — shiraz, merlot and a Cabernet Merlot blend.

“I’ve invested a lot in the quality of the wine and aesthetic of the wine brand. It’s difficult to have in every element of the chain, warehouse and the wine,” Stofile says.

She is trying to get Bellascene Wines into several restaurants and wine cellars. But, she says, the industry is not used to a high-end wine product being sold by a young black female. “I end up being questioned a lot about my knowledge of wine … I have to try to build that trust.”

Between focusing on her wine brand in the Western Cape and diamond business in Johannesburg, Stofile says she doesn’t have much of a life outside of work, but she but hopes this will change with time.

“The businesses are in their infant stages. I’m setting processes and will then eventually put the right teams together in both cities. It is difficult but it worth it because I’m really passionate about both businesses.” —